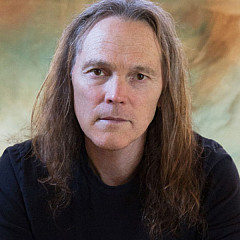

Noone still tours at 69, heading a whole new bunch of Herman's Hermits. But in addition to the nearly dozen Top 10 hits they churned out from 1964-'67, he throws in all kinds of oddities, from Johnny Cash to the Sex Pistols.

In an in-depth conversation, he told about his transition from acting to music at an early age, seeing The Beatles play in a field, meeting producer Mickie Most, his exchanges in the studio with Jimmy Page, and recording a trio of David Bowie songs early in his life.

Songfacts (Roger Catlin): You began your career as an child actor. Was that your first career path?

Songfacts (Roger Catlin): You began your career as an child actor. Was that your first career path? Peter Noone: My father sent me to the Manchester School of Music because I wanted to be a musician. There was also a drama class there at the school of music, and you had to be in it. So I'm in this class and they come over auditioning for kids to be on a TV show, and they said, "You, you, you and you." So I had an acting job. It didn't make me an actor.

Around the corner from the Manchester School of Music was this thing called Granada Television and they they were creating TV shows in competition with the BBC, so they had all these shows and they had this really successful one called Coronation Street.

And because I was a kid, and I was already in the union from all these other jobs, I got every job. I even played an Indian boy, where they put black makeup all over my body, because there were no Indian boys available — not in the union. With the money from those jobs, I invested in my group, which was called Pete Novak and the Heartbeats. I didn't think I would be an actor. I didn't even like the people in the acting class.

Songfacts: What made you so focused on becoming a musician?

Peter: It was because my family was very musical. I grew up with my auntie who played Fats Waller on the piano. My grandmother was the choir leader - in those days she was called the "choir mistress" at the church. My grandfather played the church organ really, really well and my father was a trombone player in the Royal Air Force band. There was always music, and when somebody died, or had a baby, or got married, we'd always play music together. So I was always into music.

I think Fats Waller, strangely enough, was my first taste of rock 'n' roll. Then I got into all of that Texas music: Roy Orbison, Buddy Holly, the Everly Brothers. You know, the pop music that was really in America called country music. We didn't know in England. We thought Conway Twitty was a rock star. So it was the musical pop stuff.

Some boys in my neighborhood were more into American rhythm & blues and all that, but I was attracted to the Everly Brothers, and of course we'd sit around we would harmonize, just like The Beatles did. The same inspiration as The Beatles. Because what is country music but Irish music with some German oom-pah in it? So in England we were very attracted to that, because we were all actually Irish people.

I could sing like Buddy Holly, and I could sing like Phil Everly, and I tried to sing like Roy Orbison - or I tried to because I was about 11. And that was it. People were attracted to the music that they could play. If you could pick up a guitar, you could in five minutes play all of Buddy Holly's songs, and be in a band.

Songfacts: Were you recruited into Herman's Hermits or did your band evolve into that?

Peter: There was a band called the Heartbeats. Their singer didn't show up. I showed up, because I had an incredible amount of musical knowledge, like owning records and stuff like that. We lived in a record store, almost. I had knowledge of all these songs.

Their singer didn't show up and they said, "There's Peter Noone. He knows every song in the world."

They asked me to step in that night, and I enjoyed it and they offered me the job. So I became Pete Novak and the Heartbeats. I think within a month I took control of the band, which is a kind of Nooneism: You've let me into something, now I want to take control and take over.

Me and this guy Alan Wrigley became the inspiration for what kind of music would be played, and we went looking for guys to replace the ones we had with people with who were just better, really. The band got busy, and we spent all day looking for work. I bought a van paid for by my TV thing. So we just slowly moved into this next level, which was people who wanted to be in Herman's Hermits, not because they liked the music, but because we had more work than all of the other bands, so we started to get these journeymen people into band.

Once, we saw The Beatles playing in a field. We were walking around and we were practicing and we heard some other music playing and we said, Oh some other band, or beat group was playing. We walked through this field, and in the next field was The Beatles playing. It was a soundcheck, but we thought they were practicing. We were like, How could this band be practicing? It was The Beatles. And they were doing a show there. During the show, the bass player who was my partner in the band, quit show business. He actually said the words. They were doing one of those Beatles songs off the first album, like a rock 'n' roll song, and he leaned over to me and said, "We're fucked."

But I had this opposite thing because I was panglossian Peter Noone. I was really optimistic. He left and deserted the band completely: "It's too much work." So what we decided is that we'd find people who would quit their day job and give 100 percent of their time to the band. We decided this during the Beatles show.

Everybody lives by now at my grandmother's, everybody eats at my grandmother's. We became close and got a van and off we went around the world. People think it took a minute, but it actually took a long time. There was no overnight success for us. We struggled, and sometimes we'd make enough money to eat after the show. We'd go to a fish and chips shop but we wouldn't get the fish, we'd only get the chips.

Songfacts: This was in Manchester?

Peter: Manchester, Liverpool... We broke into the Liverpool market because they liked us there, because we did odd songs. Every band was playing the same songs. We had these weird, outside songs, so we were kind of a novelty.

We did it the hard way. We'd play the lunchtimes at the Cavern because we didn't have jobs. We copied The Beatles. "Did The Beatles do that? Yeah, we'll do that as well." The Beatles did that with Elvis too.

In the 1970s, his brusque, honest judging on the British TV talent show New Faces opened the doors for Simon Cowell decades later. After being one of the most successful producers in British history, Most died in 2003 at the age of 64.

Peter: Some time earlier, we'd seen the Everly Brothers and on the bill with the Everly Brothers were the Stones and Bo Diddley. The Stones were kind of funny, and they got away with it because they did a Chuck Berry song, and we said, "That's rock 'n' roll, then."

And then there was this guitar player called Mickie Most. There were Teddy Boys and Mods in England at the time - in America, they were called mods and rockers, but in England we called them Teddy Boys. Teddy Boys liked everything American, nothing English. No English stuff was allowed. It was all Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry, Sam Cooke crept in somehow, Fats Domino, all those people.

And the Everly Brothers were in that, too, because they were American. But there was this guy on the show called Mickie Most and he came on and he did this song called "Sea Cruise":

Oo wee

Ooo wee baby

Won't you let me take you on a

Sea cruise

And during the guitar solo, he kneeled down on one leg. When we talked about making a record, we said, We should get that guy. Because he knows it's about guitars. We didn't have a piano player, we didn't have a violin section, it was just two guitars, a bass, a drummer and a lead singer. So he knew all about guitars because he had one, and he was cool because he kneels down during his guitar solos - very American.

We told our manager — this guy who never managed anybody, but we signed him because The Beatles had a Jewish manager, so we found ourselves a Jewish manager — and he got me in touch with Mickie Most in London, who at the time was an early independent producer. He came to this place in Bolton we were playing, and he came to see us there. He tried to sign me and wanted to fire the band. And I said no, no, no.

It was that trade union thing from the north of England: No, no, no. It's the band or no deal at all. He said, "OK then, I'll sign the band but you have to get rid of him and him and him and him." So we fired the drummer. We got a new drummer because we didn't know that when you made records you had to play in time. So, like The Beatles, really, the minute we changed the lineup we found out what we were. The line at the time was that you don't want to be the weakest link in this band, or Mickie Most will throw you out. So we changed it.

Lisberg signed Graham Gouldman on a retainer to write songs for the band, though his first offering, "For Your Love," was rejected, eventually going to the Yardbirds. In the mid-'60s, Lisberg managed three successful Manchester bands: the Hermits, Wayne Fontana & the Mindbenders and Freddie and the Dreamers. Lisberg later managed Gouldman's band, 10cc, as well as its successful video-era offshoot, Godley & Creme. At age 76, Lisberg is still in the business and working in Manchester.

Peter: The whole thing was, if you can make a record it will get us on the radio. On the record you can hear the enthusiasm of this band who believe that they were going to be heard on the radio.

And the end of that story is when we first heard the record, we were in that club when Mickie Most came to see us and fired all the guys. We were actually in the same place again. It was a Friday in August. We were standing in the kitchen getting changed, which we had done hundreds of times. And on the radio in the kitchen, we heard, "Herman's Hermits with 'I'm into Something Good.'" We flipped out. It was amazing.

When the record was on the radio, we thought we'd made it. Now what? Now what are we going to do? We hadn't thought beyond that.

Songfacts: You went on a big tour, right?

Peter: We'd been on tour for two years by the time it got on the radio. The record instantly went into the charts, it was a massive hit. It's still the one they know more than all the other ones, and we had lots of good ones. But that's the one they connect with the band.

It was a massive hit, it went to #1 in England, so suddenly no more £20 a night. You know, at the Cavern, we were getting the same money as The Beatles before the record. We had a following. It started with Margaret and another girl, and it grew so we could play the Cavern and 300 people would show up just to see us.

We'd seen The Beatles and there was this guy called Vic Lewis, who was an old friend of my dad's, because he was in a band from the English big band era. They just copied American records for a living. So Vic Lewis walks in the dressing room, and he said, "Do you lads want to go to the Philippines?" And we said, "Yeah!"

If I was working as a hairdresser or something, I'd never get invited to the Philippines. Yeah! We were just these naive guys. You don't realize that not one person said in those days, "How much?" We just thought, Oh, we get to go to the Philippines.

I sometimes think it could have been my stamp book, you know. I could have been a philatelist, because I was really good with stamps as well. It was a bit Asperger's - my stamp book was really organized a bit above average, and I was a stamp trader as well. That was my other hobby, outside of music, which was my real hobby, which made my mother happy, which was philately.

I probably would have been really good at that, but you don't get to travel much. All you do is go to stamp trade things with the other nerdy kids who like stamps. "I don't think they've ran 1912." "I've got this" and "I'll swap you that." It was like baseball cards in America.

So I was lucky my hobby turned into making a living, but I didn't ever do it to make a living after that first period where I had to make the payments on the van. Once we became famous we realized we didn't do it for money. We'd always undersell ourselves.

That first tour we got offered was Dick Clark Caravan of Stars. The agent told me at the time, "I can get you this big thing." And by then it was, "How long is the tour?" He said it's 48 dates. And how much does it pay? He said, "I could get you $500 a night." And I thought, $24,000? I'm in!

We never asked, What about airfare or hotels? Five hundred bucks a night and we were allowed on the bus, which was a Greyhound bus which we rented with 40 other people. We had the best time of our lives. We thought that was going to be our last tour. Everybody in those days thought, This will be over in 10 minutes, won't it?

Songfacts: This was in 1965?

Peter: Yeah, early '65. We took it because we called the agent in America, and by the time we got past all those people who'd say they'd call you but were never calling you back, I'd say, "This is Herman from Herman's Hermits, we've got a #1 record in England. We want an agent in America, right? Who have you got?"

"Freddy Cannon and Gary U.S. Bonds."

I almost fainted with shock because those are the two biggest stars in my head. We signed with the agent, and he was a good agent. We took Jimi Hendrix to him, The Who and Led Zeppelin. He ended up managing three of our favorite bands. Because he had Freddy Cannon and Gary U.S. Bonds, he got Herman's Hermits, and we brought The Animals, and we brought The Who and Jimi Hendrix. And even Led Zeppelin went with him because he was a good guy. [This agent was Frank Barsalona of Premier Talent Agency.]

Songfacts: You were sort of the transition between '60s British Invasion pop and the more experimental psychedelic rock that The Beatles and even The Monkees tried.

Peter: We didn't know. Before that and during the real British Invasion none of us were competitive. We all believed that there was plenty of space in the music business for each of us, because when we did those clubs in England and traveled around England, we'd see these great bands but we were all uniquely different.

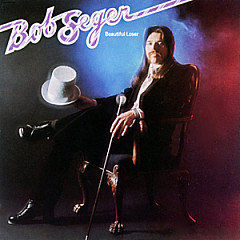

Manfred Mann wasn't like Herman's Hermits; The Who weren't like Herman's Hermits and The Rolling Stones, who weren't like The Beatles, so we didn't think there was any competition because we never knew taste would change so drastically. John Lennon would hear Bob Dylan and he would decide he wanted to be the voice of the people. Before that, it was all pop and "I've got a great song, let's record it."

And then, guess what, they want us to make an LP. Wow, we must be really famous now! An LP! We get to sing all of the songs we do in our setlist on one record. Wow.

We didn't know that the music business would change from Bobby Rydell and go to Jimi Hendrix. There was nothing in between them but The Beatles and that joyous popular music period where even your mom would say, "They're not that bad. I kind of like Paul, he's cute." It was that kind of period.

Before that, it was all 16 magazine, then it all went to Creem, Rolling Stone magazine. Judge people on their standards.

Before, we were all just musicians and you'd judge people on their standards. Just like the olden days. You could like Woody Herman and you could also like anybody else. Nobody was like, "Oh no, I'm just a Woody Herman guy." People don't realize if you look at somebody's iPhone, they've probably got some ZZ Top, some Stones, in my case even some Andy Williams.

Herman's Hermits' version in 1965 used only the chorus, sung three times ("Second verse, same as the first"). The band also altered the spelling in the title to "I'm Henry VIII, I Am," though the name of the old king is still pronounced with three syllables: hen-er-y.

It became the band's second #1 single in the US, and the fastest selling single in history at the time. Oddly, it was never released as a single in the UK.

Peter: I have the original Harry Champion recording of that, on wire. It's from a time when people were just lucky enough to be in the music business. If they hadn't recorded it, it would still be part of British culture, that song.

"Mrs. Brown You've Got a Lovely Daughter" was in a movie, so it never counted in the playlist - you could play it without paying royalties because it was a movie track.

It's just part of music culture. Remember, if you were at my house you'd get [German-British soprano] Elizabeth Schwarzkopf and Fats Waller and a lot of that hymn stuff that my grandfather liked. Because of the BBC we were exposed to multiple types of music, and rock 'n' roll was only 30 minutes a day. Now it's 24 hours a day, and that's too much.

Songfacts: You recorded some other old English ditties, like "My Dear Old Dutch." Did you do that at first to fill out your albums?

Peter: There was a thing in England called the EP, the extended play record, and what you would do if you wanted to make lots of money, the label would cut a good song with three rubbish songs, or in our case, songs that we wrote or owned the publishing.

I went to my 48th wedding anniversary the other night. We used to do this song before I met my wife called "My Dear Old Dutch," which is short for Duchess - it doesn't have anything to do with Holland:

We've been together now for 40 years

And it don't seem a day too much

Cause there ain't a lady living in the land

That I'd swap for my dear old Dutch

Very romantic. When I sang it, I was impersonating an old man. And now that I've been married 40 years, I don't feel as old as that guy who first sang it.

But it's just a part of English culture to know songs like "Oh, Mr. Porter."

Oh Mr. Porter

What can I do?

I wanted to go to Manchester

But I ended up in Crewe

It's from another period and a culture I grew up in where there were trains and people did fall asleep on their train and miss their stop and ended up somewhere else. And part of my attraction to America during that period when I was recording those was, like, Chuck Berry, singing about Memphis, Tennessee.

This man and Bob Dylan were writing these phenomenal poems about America. Every kid in England listened to those songs and said, Wow. Memphis, we didn't think about Elvis, we thought, "Long distance information" and the brilliance of those songs. He had this great way with words and "Promised Land" and "Roll Over Beethoven" were all perfect stuff for us. And those English songs were written by people to describe that part of the world as well. Music connected all the dots for me. Like, I get it now.

Last week the man of the moment was Herman, 16, of Herman's Hermits. An engaging high school dropout who looks like a toy sheep dog, Herman (real name: Peter Noone) smiles a lot, claps his hands over his head, and sticks his finger in his mouth when he sings. His "Mrs. Brown, You've Got a Lovely Daughter," rendered in a heavy English Midlands accent, was the #1 bestseller last week.

Songfacts: The very Englishness of your band, stressing the British accents, was that part of its appeal in the US?

Songfacts: The very Englishness of your band, stressing the British accents, was that part of its appeal in the US? Peter: They were songs that were based on the logistics of the person. When we did them in England in the early days, the audience knew what we were doing. We were just lucky when we came to America, everything was about England.

I got off the plane one time and there was this song, "England swings like a pendulum do, bobbies on bicycles two by two." It's a country singer singing this brilliant song about Westminster Abbey, the tower of Big Ben. I was like Wow, this guy just made a billion dollars for tourism! And Twiggy was in the papers and there was a Time magazine cover, it was me and The Supremes and The Righteous Brothers. It was like: How did we get into this? How did this happen?

We came over here and in 1965, they put out 11 singles in one year. And then the promotion guy says to me, "Your record is the first one that didn't make the Top 10." I go, "You know what? There's three other records in the Top 10 right now. If one only got to #11, maybe you put too many out; you could have saved that one until next year." Will there be a next year? Sometimes you didn't know.

Songfacts: Your music seems to have lasted.

Peter: I knew Jack Bruce since 1962 - a long time. "How long did you know Jack Bruce?" somebody asked me when he died. "52 years," is what I said that day. Me and Jack Bruce were just drinking partners. We played each other's records. I bought all of his records, I'm sure he bought none of mine. But we were still friends. I remember he said he liked "No Milk Today," and I thought, Of all the songs I made you only liked one? But he was a friend, so I let him get away with it.

Songfacts: "No Milk Today" was by Graham Gouldman, who also wrote your "Listen People" and "East West." But you had the pick of a lot of songs from writers ranging from Ray Davies, to P.F. Sloan.

Peter: Graham Gouldman's songs came to us because our manager was his brother-in-law. He was a friend. We were this odd band that got gigs wherever we asked for gigs really. We'd say we'd play for nothing and if you liked us you could pay us. We were pretty persistent. We used to play this place, and our friend was in the Mockingbirds, which eventually became 10cc and all that. They were one of the greatest bands around, as great as the Undertakers in Liverpool, but they were kind of stuck on this circuit. They recorded "For Your Love" first before the Yardbirds. But my manager married one of the sisters and Graham married another one of the sisters. It was almost like nepotism - we all knew each other.

So we got every Graham Gouldman song first. Every one of them. We did "Bus Stop" first, we did "For Your Love" first, we did "Listen People" first. We didn't do "Pamela, Pamela," because that wasn't our kind of song. Even though it was written for us, it went to Wayne Fontana.

"Bus Stop" went to the Hollies before us, because Graham didn't think it was the kind of song that we would like. Then when we heard it, it was like, Are you kidding me? We want that. Luckily John Paul Jones heard it when we were trying to figure it out and he said "Nah, I've got it," and he re-invented the song. That's John Paul Jones who turned that into a hit record, nobody else. It is not a hit song. If you listen to the Hollies demo version of it, it's just not good. He reorganized the song and made it what it is: serious art work.

Songfacts: What about P.F. Sloan?

Peter: We were in Los Angeles and they were giving us all of these songs. I kind of liked them, they were by [Ben] Weisman and [Sid] Wayne, who had written for all these Elvis Presley movies. The producer was the same guy who'd made all the Elvis Presley movies, so we weren't quite confident with these songs. I thought I'd be like singing "Viva Manchester" or something.

There is no Place Like Space was the name of the movie and there was a song called "There's No Place Like Space" [sung with the melody of "There's No Business Like Show Business"] and we thought that was quite derivative. So Mickie Most shows up and says, let's get some songs.

So we call all the people. We were all at the Beverly Hilton Hotel - we thought that was the posh place and we took over the pool section. Historically that's where all the bands would play for years and years, and we were all there. People would come over. P.F. Sloan came over and every song he played, Mickie Most said, "We'll have that one, we'll have that one."

We took every song he had. Every single song he played for us that day we recorded. Actually we recorded them all the same day we went to Capitol Studios. It was just a full-on rock and roll band experience. He was playing guitar and the Hermits were in top form playing "Hold On" and "Must to Avoid" and stuff. They were pretty great.

We were a pretty tight band because we'd done hundreds of gigs. We'd decided who we were at that time - the guitar player is great and he's weak, so we'll double track him, so we were in good shape. That's how we got that.

Ray Davies signed a deal with Allen Klein, and Allen said, "You know, you have all these songs sitting around, I could get people to record them if you just give me all the money."

And he said, "Prove it."

"I'll get an artist to record one of your songs."

And Ray says, "I got this great song for Herman called 'Dandy.' It's about chatting up all the ladies and that."

"Yeah!" So we got it and if you hear his version, my version, we fucking nailed it. We got it absolutely perfect. It was believable.

We go back to Stanislavsky. When Mickie Most was in the studio, he never said, "Louder, back off the mic." He said, "I don't believe you." Brilliant! Because in those days, record producers weren't actually producers, they were directors. They directed the records.

The producers of course get the money and all that, but he was the director. "Put him on the left-hand side of the mix" and all that — that's direction. He's brilliant at that. And his biggest, biggest asset, was that he knew hit songs when he heard them. "Oh, that sounds like a hit!"

I would always say the key wasn't right for me, but he'd say, "No, Peter. If I can sing it, everybody else can sing it. So we'll do it in my key."

Songfacts: A lot of the Yardbirds stopped in to play on your recordings. Did you appear on other recordings in the studio too?

Peter: We were all over each other's recordings. I'm on a lot of Donovan. Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones are all over Herman's Hermits. At the time, it didn't seem inappropriate. It wasn't like we were The Monkees - we were bands. And if somebody could come in and do it quicker and better, we never second guessed that.

You know, "Jimmy Page is next door doing the Honeycombs or something, let's get him and play a lick on this."

"How much does he want?"

"Nine pounds."

He was a guitar player who worked for £9. We had £9, by a stroke of genius, so it happened like that.

Like Clem Cattini, the drummer on "Wonderful World." Sometime in the '70s when I ran into him, and everyone was starting to wonder why they weren't getting paid, I said I feel bad about that record, because he and Jimmy, they cut the intro. It's Jimmy Page, going bom- bom bom bom bom, bom- bom bom bom bom. Jimmy said, "It's boring. Let's cut it in half."

I didn't get that memo. So they're all playing, and they got to the chorus and I was still in the intro. I never caught up on the record. But we only did one take of stuff in those days because Mickie would say, "Oh yeah, that's got a great vibe" without really being perfect. The imperfections of Herman's Hermits are what made it of the moment.

Nowadays, in the music business, we would take Clive Davis "Henry the VIII" and he would say, Why don't you write another verse? We're not putting it out unless you write another verse. Or put some strings on "Mrs. Brown You've Got a Lovely Daughter," and make it more understandable. Get rid of the accent.

People started to change things and do overdubs and stuff. We didn't like any of that. We wanted to be real and be able to play the songs on stage that we had recorded. We never got a trombone in the band and we never got a girl singer. We never had girl background vocals.

Songfacts: You put some strings on some songs.

Peter: Yeah, but we didn't pretend to do them on stage later. We did them without and the guitar player played the lick. It just became the live version of the recording.

We didn't have a piano. We had a piano on "We're Into Something Good," because there was something missing. So Mickie said, "There's this guy Roger Webb. He's in the next studio."

He came in, and he thought it was surf record, so he thought he'd put a surf vibe on it: "dat dat da da." He was in the Roger Webb Trio. He was a jazz player, but he happened to like Herman's Hermits' pop style. He said, "Let me put this on it," and we ended up following him.

Songfacts: You never went into an experimental mode.

Peter: Everybody did that. It's like everybody did disco. We didn't do that either. One of the low points of music is the Beach Boys disco versions. All of those brilliant records with a disco beat? Nah. We never did that and we never wanted to do it. And no rap singer ever steals a bit of a Herman's Hermits song and puts it in their song. We don't want that. They are what they are, and the music was made for the moment it was made.

In those days, you could make a record. See, it was all singles. Albums were something you made when you had a lot of hits. But we could make a record on Monday and have it on the radio and in the shops on Friday. Based on that moment in time. If you put "I'm Into Something Good" out today, no one would even hear it, but when it came out in England, it was exactly the right thing, at exactly the right moment. And all the other ones, as well.

We put out an EP with "Mrs. Brown You've Got a Lovely Daughter" and "Sea Cruise." The EP had four songs on it, twice as much as a single, so it was kind of a con job. Americans wouldn't do that. They wouldn't buy a two-for-one special if it cost three times as much as one. So we were not making records for America, we were making records for England. We only knew British people. We didn't know what Americans liked.

Songfacts: The band seemed to disappear from the charts after 1968.

Peter: That's not really the case. We kept going in England after we stopped putting records out in America. We had a #1 with "My Sentimental Friend," which I don't think was even released in America. The label that we were on went bust.

It all changed very quickly. We'd do the records and they wouldn't promote them, so we decided we were not giving them records. In England we had massive hits after '67. I think our last hit in America was in '67. We had "Sunshine Girl," "Sleepy Joe," "Years May Come," "My Sentimental Friend," "Something's Happening" — all massive songs in England, bigger than everything except "I'm Into Something Good."

So it's just different. America was just five percent of our market and we were allowed to only play 50 days a year in America because of the union. You were legally only allowed to do 50 days a year. But in England, we went everywhere. Everywhere The Beatles went, we went, because we were next up. Who's next? Oh, them. The Monkees never did that because their TV show was only on in America, and they were only famous in America. When it came out in England, they became famous in England.

The records all came out on the same day in those days, but we only made them for England. We had no idea what you were thinking. I only knew my sister, and I knew my sister really well, so I'd ask her what she thought of the record. I wouldn't ask anybody else.

Songfacts: I wanted to ask about your recording of "Oh You Pretty Things" in 1971. Was it issued before David Bowie's own version?

Peter: I think we recorded it first. What happened was, he had this song, and he went over to Mickie Most's office and he played it. Mickie and Peter Grant, who was Led Zeppelin's manager, shared an office. I saw Ronnie Wood from The Stones the other day, and he remembers standing in between those two desks and fighting off all that English comedy between them — "Do they make that suit in your size?" and all that.

David Bowie had played this song. Mickie was really a big fan of Bowie, because he liked that Tony Visconti record "Space Oddity." He had a couple songs and Mickie said, "I want both of these songs for Herman's Hermits."

We went to the studio, and by then Herman's Hermits were not on any records - Mickie and I were making records on our own. Mickie said, "This should be your first solo single," and I said OK.

We tried to record it from the demo which was just David on the piano, but the piano player just couldn't get it. We had Herbie Flowers, the world's greatest bass player, and the best people in the studio, the best drummer and everything, but nobody could play the part that David Bowie played because David played it in F sharp. He could only play on black keys. And for normal piano players, that's unusual and difficult. We wanted to record the song in F and nobody could do it.

Mickie said, "Let's get Bowie over here."

David comes in. Bowie says, "I can't play it all the way trough. I get tired. I'm not a real piano player."

So Mickie says, "Let's record one section and then we'll cut the tape and repeat it three times."

David says, "That sounds like a good idea."

So he plays it perfectly once, everybody loves it, it's a great version, then we repeat it. It was one of the first bits-and-pieces type of recordings. David played it great once and we worked around that. We just put the vocals on it and Mickie put some violins on it that night — I don't know why, we didn't need them. But he said, "I put some violins on it, if you don't like it we'll get rid of it." But of course they never got rid of anything if they spent money on it. So there you go.

It's pretty funny. They put the record out, and they bought this massive, massive Trafalgar Square picture of Peter Noone, "Oh You Pretty Things." And Trafalgar Square, in those days, every bus in London went past this massive billboard. One day we see this picture of David Bowie standing in front of the billboard, all proud, saying, "My song!" Great.

We did another Bowie song: We did "Right On Mother." That was probably ahead of its time. We thought we could do another "My Boy Lollipop." But wait a second, a man sings a song to his mother, it's not like "Mrs. Brown," it's the opposite. He's singing it to his mom. Didn't work. Wasn't a hit. Maybe it wasn't as good a song as the other ones. [It ended up as B-side to the song "Walnut Whirl," co written by Herbie Flowers].

And we did this other one. Bowie had a song called "Bombers," which was, "All clear, goes the captain." RAF captain. I loved it because my dad told me all these stories about flying over Germany and bombers. My dad was not into singing songs about peace and love because he'd have to go bomb the shit out of people who were hating each other.

Songfacts: When you play concerts now, you throw in all kinds of other things other than just the Herman's Hermits hits.

Peter: I don't want to fall into the trap of having a set list. People get into the rotation thing where they know what the next song is. I'm talking about people on the stage. So if I shout out songs based on the way I feel the music is going, there's a construction going on.

And then we do somebody else's song, "Love Potion #9" or "Do Wah Didddy," a song that isn't Herman's Hermits, so that more of the audience can sing along in the breaks of the songs. If they can sing during a break in "Love Potion #9" on their own, they will. And then they think, Oh, this is going to be fun. I'm going to be allowed to sing and shout.

You go to see a Stones show, and everybody sings "Brown Sugar" all the way through. And "Jumping Jack Flash," even with the wrong words. But they all sing. We don't have one of those. You can sing along to "Something Good," but I'm singing all the time through that.

You've got these songs where I'm not singing but you can sing. "Do Wah Diddy" is perfect for that.

There she was just a walking down the street singing...

Do wah diddy diddy dum diddy do

The audience sings it. Just to make it a comfortable thing.

Then I don't know what's going to happen until we get to "Can You Hear My Heartbeat," "Mrs. Brown," "Henry the VIII" and "There's a Kind of Hush." We have 300 songs in that space. Three hundred. We know 300 songs. We do "Because" and "Glad All Over" by the Dave Clark Five. We do "I Will" by the Beatles and we play it just like "Mrs. Brown" - it's got the same guitar sound. We do it as if Herman's Hermits had recorded it.

We do "White Wedding" and we do the Sex Pistols doing "Jingle Bells." We've got so many different things. We've got "Pretty Vacant." We have a "Hey Ho, Let's Go" moment.

We do what I feel like really, and what it does is it keeps everybody in the band alert. Sometimes "What the fuck is he doing?" looks like enthusiasm. People are not actors. "What's next?" They have this look of enthusiasm on their faces.

We've been doing "For Your Love" a lot lately and "Bus Stop" because there are some people who hold up albums and I'll say "Let's do some of the songs on this album — oh look at this, "Bus Stop." My drummer likes to do a drum solo, so we do "For Your Love" so he can beat the shit out of his drums. It's fun stuff, and it has to be fun.

I say the best fun I ever have is on stage. the rest of it is not that much fun you know: Going to the airport, getting a parking spot, getting to the airplane. Because I'm like Chuck Berry on the road - I don't want anybody with me. I want to be in a rental car, on my own. I can listen to any radio station I want to and I can not talk to people if I don't want to. I never stay in the same hotel as the band - I stay like a hermit, and it saves all my energy for the show.

I don't want to talk to people on the plane and give my biography, so when they ask what I do, I've been saying Chippendales dancer. That usually shuts them up. I don't know why that works, but it works pretty well recently.

December 7, 2016

Get more at peternoone.com.

More Songwriter Interviews