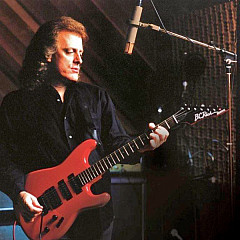

By the time he was 21, he was producing The Cure's soon-to-be-legendary Pornography album and going on tour with the band as a bass player. After fronting the band Johnny Hates Jazz and producing his own solo album, Swamp, in 1988, Phil came to an important realization: "I am a studio person."

The ensuing decades brought him success as a songwriter with Natalie Imbruglia's smash cover of "Torn," which he co-wrote, and pairings with Bryan Adams and UK pop star Pixie Lott, among others.

When we caught up with Phil, he was taking a break from the studio and enjoying a sunny day in his garden while his dog chased the occasional squirrel. He gave us a glimpse into his storied studio past with The Cure and shared his thoughts on producing, songwriting, and the "Torn" phenomenon.

Amanda Flinner (Songfacts): Did your interest in songwriting and your interest in performing emerge at the same time?

Amanda Flinner (Songfacts): Did your interest in songwriting and your interest in performing emerge at the same time?Phil Thornalley: Yes, I suppose they did. Once I started learning guitar, a very close friend who I grew up with who's also still in the music business, we kind of started together. Once we learned three chords we wanted to write songs. That was very much the passion, to be a songwriter more so than a performer.

Songfacts: What type of music were you interested in at the time?

Thornalley: For pop songs, it was The Beatles, but mainly I was interested in an American artist called Todd Rundgren who is still going, but in the '70s he was just making some fantastic music; transcendental, just trippy and brilliant. [Rundgren is indeed still going strong and pushing the boundaries - we spoke with him a few months ago about his latest project.]

Songfacts: So then how did you end up at RAK Studios?

Thornalley: I applied for a job there and was really lucky and got the position, mainly because the band that I was in, we'd kind of figured out how to record ourselves. Because I wasn't going to succeed as a songwriter when I was 18, my mum actually was very keen that I should get out of the house and get a job, so I was lucky enough to start at RAK when I was 18.

Songfacts: Was it typical for people to start that young?

Thornalley: Yeah, it was very much like what we would call an apprenticeship here [in England]. I finished high school and went straight to a job. In the recording studios in those days you started as a tea boy and then became what was called a tape operator, and then you worked your way up the ladder to becoming an engineer or a mixer or a producer. In those days I think there was one engineering course that the university offered, but it was more about electronics. Now, of course, there's just thousands of courses you can go on to learn record production and engineering, but back then there was nothing.

It's much better to learn on the job, I think, but that's my view as an older person.

Songfacts: Moving on to some specific songs, what do you remember about working on the Duran Duran hit "Is There Something I Should Know?"

Thornalley: Well, I used to work closely with a producer called Alex Sadkin when the offer came to remix that record. Duran Duran were super-hot then, they were the biggest band in the world, and I think they'd tried everyone to mix it. It was just another job that came through, and I just happened to be on fire that day and did a really good job. That worked out well so Alex then produced the album that followed, which was called Seven and the Ragged Tiger.

To boost its pop appeal, the group recorded a more radio-friendly version of the song, which was produced by Chris Kimsey. The movie was a hit, and its title song entered the psyches of throngs of American teenagers who associated it with the emotional stew Hughes cooked up in the film.

Listen to the song, however, and you'll hear that the lyrics bear no resemblance to the plot of the film. "It was nothing like the spirit of the song at all," Furs frontman Richard Butler told Mojo. "It's really hard to say whether it was damaging for us. I suppose we got tied in with the story of the film, and if that's what people thought the story was about, and didn't look much further than that, they were getting a very false impression."

Thornalley: I thought the later one was great. The main thing was that they finally had some worldwide success.

I worked on the first two Psychedelic Furs albums, and I just didn't really ever imagine that they would achieve that kind of breakthrough to that type of success - it was a very arty kind of band. That new version of "Pretty in Pink" probably did them really well in terms of making a living.

Songfacts: I spoke with Robbie Nevil recently and he was talking about working with you and Alex Sadkin on his debut album and how it was a really good learning experience for him. Do you have any memories of working on that?

But we worked him really, really hard. When I say "we" it's because Alex Sadkin was co-producing with me, and we gave him a hard time with his singing and made him do lots and lots of takes and then come in the next day and do lots and lots of takes. But that's because we were just trying to make the record as good as it could be.

So, I'm surprised he remembers it as a positive experience. I guess if he said it was a learning experience that's a very diplomatic way of saying it.

Songfacts: Well, he did say how frustrated he was at the time, but he was remembering the experience in a fond way, not in a way that was bad.

Thornalley: The thing is, when you actually have the hit then you forget about the frustrations. Yeah, everybody got frustrated, but we had a major hit, which is always fantastic when that's what you're trying to do.

Songfacts: So you worked with Alex Sadkin and you worked with Mickie Most and you worked with Steve Lillywhite. How did those experiences shape your own philosophy as a producer?

Thornalley: I think I took something from each of them. Mickie Most was brilliant at spotting hit songs. Because his success was in the '60s and '70s, the thing that he did, he would just narrow in like a laser beam on having a hit single. It didn't matter who the artists were, they could be like a pop band or a credible band, he just lasered in and all that mattered was that they had a hit single, because if they didn't have a hit single, there wouldn't be another album. These days I think everyone considers that normal, but back then it was considered a bit brutal.

Then with Steve Lillywhite, he could take a band like The Psychedelic Furs, who weren't great musicians, and he could create such an atmosphere in the studio of kind of gung-ho, positive, we can do this, that it would raise their morale, like a football coach would. The sum of their talents, which was not great, would suddenly become something quite outstanding, and I saw him do that with a few bands.

Alex Sadkin was much more meticulous and was a fantastic recording engineer himself. I guess all of those producers were looking for hits, but with Mickie it was a real, real focus on the hits, with Steve it was more about getting excitement on the tape and then maybe that would be a hit, and then with Alex it was a very considered, almost scientific: "Let's see if we can turn this into a hit. It doesn't sound very good right now but let's see if we can pull out all the stops and turn it into a hit."

I'd like to think that I took those key factors from them.

The album is now considered a proto-goth rock classic by fans and critics alike, but its production has inspired larger-than-life tales, from the Cure barricading themselves in their record label's offices and building trash heaps and beer can pyramids in RAK studios to refusing to work until they snorted ample amounts of coke or dropped acid. Smith claims he barely remembers making the album, but calls it one of the group's best.

Thornalley: Totally. I actually produced that very early in my career. I was like 21 and it was before I'd worked with Alex. Robert has gone on record saying that it's one of his three favorite albums. At the time, it was just another album that was made along with The Psychedelic Furs or Hot Chocolate, but with that one I think because I was at the same age as the guys in The Cure, we were more like contemporaries and all the nutty stories you've read about the making of the record, they're all true. It was just over the top.

In the end there was no hit single, but there was this great legacy of this album that you put on and you go: "That's something different." So I'm very proud of that, but the mythologizing, I guess maybe it has got something special about it: it's so different, it's so not what anybody was doing then or not what anybody's doing now. So, long may the myths continue!

Songfacts: I read how you guys stumbled upon the pornography debate between Graham Chapman and Germaine Greer that is sampled at the beginning of "Pornography." But was that track already written when that happened?

Thornalley: Yes it was. It was just one of those freaky things that has happened in my career in the studio where we tried this approach that Brian Eno and David Byrne from Talking Heads were doing. They called it "Found Music." You turned on the radio or the TV and tried to find some disparate elements and sometimes it just worked.

I suppose in this case it was very literal. You know, I don't know what the song was about, but the title was "Pornography." But we happened to try this experiment coincidentally just as this highbrow program was discussing the subject. So it's just weird.

Songfacts: That's crazy. I don't think kids today would realize just how much of a coincidence that would be because they don't have that experience of flipping through channels without any kind of guide. Plus, you can just search on YouTube.

Thornalley: Of course, you're right. It happened one other time too on a Thompson Twins record where we did the same thing, but this time we turned the radio on. The song was called "Judy Do" and it was about Judy Garland. We thought, "Oh, let's do something weird in the middle of this song. Just set up the radio and let's just tune it in." And we tuned it in and it was Judy Garland singing.

Like you say, now you'd go, "OK, we're doing a song about Judy Garland, let's go on YouTube." Then obviously it wouldn't be so much of a coincidence, but that was just one of those freaky things.

Songfacts: At what point did the songwriting and producing aspect become more important to you than trying to be a performer?

Thornalley: Well, I was always writing songs, but the ones I released myself had no success. It took a while to figure out that I should stop trying to be a performer, which I didn't have any talent for, and I'm not saying that in a modest way. It eventually occurred to me that I was good at producing, and I really enjoyed writing songs, so why not just concentrate on those?

It took a long while, but luckily with the success of Natalie Imbruglia's "Torn" record, I finally reached where I'd been trying to get to from the time I was 12. I was now a songwriter, people respected my songs and would sometimes ask me to produce them, so that's what I'd worked towards.

Songfacts: After you made that decision, did performing become more enjoyable when you did play for other artists?

Thornalley: Yeah, it really did. From that point on I stopped making records for myself and I appeared on other people's records, like Bryan Adams, playing guitar or drums. And the massive success of the Natalie Imbruglia song, it gave me just so much confidence. Like all artists, you tend to be insecure when you're not being arrogant. So it's true, it freed me up to enjoy my music more.

Songfacts: Well, since you mentioned it, how did "Torn" originally come together?

There was also an A&R man in Denmark called Poul Brun who was such a genius and so positive, and he always loved that song before anyone else. He was the first person to use it with a Danish artist, and then he used it again with a Norwegian artist who had some local success with it in Norway.

So, it's six years after the song has been written that I met Natalie. My publisher introduced us and said, "You should do 'Torn.'" And that was a great idea.

Songfacts: Why do you think she hit big with that after so long when nobody else did?

Thornalley: Sometimes you have to wait for all the elements to come together. Obviously, she was a pop star and had a background as an actor so she looked the part. She knew how to make a great video and the quality to her voice seemed to suit the song because the song is quite anxious, and yet her voice is quite sweet. So, I think that made it an attractive union of emotions.

Songfacts: And then you also wrote songs together for the album (Left of the Middle) too, right?

Thornalley: Yeah, we did. It was a really successful time. We probably wrote about 10 or 15 songs, and five made it to the album. That's a pretty good success rate if you're writing songs. It was a really, really good time, one of those times where you're writing with someone, and you feel a lot of freedom to speak honestly with each other and try to make it the best it can be. And then success happens and everybody goes crazy.

Songfacts: Did you get the feeling when you were hearing it that it was going to be something big?

Thornalley: No. To me, it was a surprise. It was a phenomenon. It was beyond what all of us had hoped for. There was a radio station in London that started playing it, and then it just snowballed from there.

Thornalley: No. To me, it was a surprise. It was a phenomenon. It was beyond what all of us had hoped for. There was a radio station in London that started playing it, and then it just snowballed from there.I will tell you a story about when Natalie's album was about ready to come out. It had been made in London by RCA, which was part of BMG then, and they took it to the American record label - and everybody passed on the record. Everybody in the US said, "No thanks." And then, of course, it became a massive hit here in the UK, and the very same A&R man who had said "I don't want it" in New York was now trying to get his name put on the album to say that he was the executive responsible for it. That's the music business. That's quite cynical but it's true. That's how it works.

Do you know that Rudyard Kipling quote about deceit? "Victory has a thousand fathers and defeat is an orphan." Something like that? Of course everybody was going, "Yeah, I was there, I helped get that one done." Because it was such a phenomenal record, it just was a smash all over the world. It was just fantastic for my career and for Scott and Anne and everyone associated with it.

Songfacts: What is your songwriting process like?

Thornalley: I tend to write a lot by myself now, but I don't know if I have a process. Often the record company will say, "Would you like to work with this artist?" And then it can be lots of different ways.

But I take it a lot easier these days. I used to write with artists all the time and now I'm very choosy. Like Bryan Adams, I'll still write with him, but there are not many other people that I will go "Yes!" to immediately. I like to write songs just at the piano, come up with ideas or catch a melody somewhere after riding the bus.

You never know what people are going to ask for. I did music for a musical a few years ago, and then I've done music for commercials. I kind of go, "Yeah, I think I can do that." Then that's what I do.

Songfacts: When you do work with other writers, do you like to bring something or having something in mind going into the session?

Thornalley: I used to do that. I used to think it was totally necessary to have a song half prepared, or have a chorus, and have a few ideas to play to the artist, but over the years I'm a bit more relaxed. Often it will be like, "Let's just start something from scratch and see what happens, see if it's our lucky day."

So there's not so much anxiety about it because oftentimes when you're writing with people, you get that sinking feeling that this isn't really the best song, but you know what, let's not worry about it and just finish it. Rather than go, "Ugh, come on." It's just go with the flow. It usually comes out pretty good, most of the time.

Songfacts: You also did a few hits for Pixie Lott, and that was your first time writing with Mads Hauge, right?

Songfacts: You mentioned Bryan Adams earlier. What do you remember about the song "On A Day Like Today"?

Thornalley: Oh, I love that song. Because of the success with "Torn" I got the phone call: "Would you like to work with Bryan Adams." And I was like, "Absolutely!"

He lives in London and I went round to his place and we had a little songwriting session. It went OK but I had this feeling I'd missed a chance, so I was about to walk out the door and I said, "Do you know what, I've got this one other song, let me play it to you." Then he was like, "I love it, play it again," and that solidified our partnership. You know, I'm still working with him 15 years later.

He just loved it. I think it was different from the stuff he was writing at that time. It wasn't straight-ahead rock, it was a bit melancholic, and I think we made a really good record out of that. It was successful here, but it wasn't so much of a success elsewhere. But it was one of those last-minute things where you go, "Just before I go let me play you one more idea." So that worked out well.

Songfacts: And you guys also wrote "The Way You Make Me Feel" for Ronan Keating. Was that specifically written for him?

Songfacts: Lastly, how has your view of the music industry changed after almost 40 years in the business?

Thornalley: I don't think too deeply about it. I'm happy to still make a living, and be in music. Everything changes in life, you know. In 40 years the farming business would change and the car industry would change. Of course, there's the loss of revenue from the illegal downloading, and then the poor royalties from streaming sites, but I think you've just got to move on and write a better song. Max Martin seems to keep writing number ones in America, so I don't think you worry about illegal downloading when you just keep writing your songs that everybody wants.

September 22, 2015

More Songwriter Interviews