Born and raised in Honolulu with a stop in Kansas City, Dean Pitchford returned to the mainland to study at Yale, where he earned a degree in English literature (class of '72). New Haven is 90 minutes by train to New York, where Dean landed a role in a production of Godspell his junior year. He got to know the legendary songwriter/stage actor Peter Allen, who augmented Dean's Ivy League education with advice on how to write song lyrics that help define characters. After performing in Pippin and at least 100 commercials, Dean got a big break writing lyrics for Fame, and the title track, performed by Irene Cara, was a huge hit, going to #1 in the U.K. and #4 in America.

Dean's next stop was Warner Brothers Publishing in Los Angeles, where as a staff songwriter his compositions included "Don't Call It Love" (later a hit for Dolly Parton) and "You Should Hear How She Talks About You" (a Grammy-winner for Melissa Manchester). Around this time, Dean started working on the screenplay for Footloose, the story inspired by a newspaper article about the town of Elmore City, Oklahoma, where they had just lifted their 80-year-old ban on dancing.

These days, hardly any hit songs emerge from movies, but Footloose had an astounding six hits, all with Dean's lyrics and written specifically for the film. The songs got a reboot in the 1998 stage production and in the 2011 remake of the movie, whose director, Craig Brewer, had the good sense to consult Pitchford and retain the spirit of the original.

Some of Dean's other accomplishments include the Whitney Houston hit "All The Man That I Need," songs for the movies Beaches, Chances Are, and Shrek 2, and lyrics for the stage revival of Carrie.

Dean's extraordinary talent for finding the right words might be a byproduct of his compassion: Richard Marx told us that when he was stuck for lyrics on his song "Heaven Only Knows," he called Dean, and without writing a word, Dean talked Richard into a place where he knew what to write, "maybe the ultimate gift anybody's ever given me," said Marx. Kenny Loggins, the biggest soundtrack star of the '80s, worked with Dean on the song "Don't Fight It" before he agreed to do Footloose, which found the pair writing the title track in a Tahoe hotel room while Kenny was nursing a broken rib. If you look at Dean's career, a pattern of benevolence materializes. He certainly understands human nature, but it was years before he realized that his most famous work came out of his own upbringing.

Carl Wiser (Songfacts): Because you're doing Carrie, I read a little bit of the Stephen King book where he talks about how he approaches writing. He was talking about how many times he'll write something and then he'll look back on it, and he'll realize that there was a piece of him in the writing, perhaps a character. Has anything like that ever happened to you?

Carl Wiser (Songfacts): Because you're doing Carrie, I read a little bit of the Stephen King book where he talks about how he approaches writing. He was talking about how many times he'll write something and then he'll look back on it, and he'll realize that there was a piece of him in the writing, perhaps a character. Has anything like that ever happened to you?Dean Pitchford: Oh, all the time. It's inevitable that you are drawing from your own experiences. Sometimes it's very conscious, other times it's totally unconscious on my part. I had one of those forehead-smacking experiences when I was asked to speak at a seminar in Seattle for a film festival. This was about two years after Footloose opened, the original movie in 1984. I was picked up at the airport by an intern who on the way into town was making conversation. He'd obviously done his research, and he asked me whether or not my writing Footloose had anything to do with the fact that when I was a teenager, my family had been uprooted - I had grown up in Honolulu and I moved to Kansas City, Missouri, where my father had gotten work, and I was really a fish out of water there. He asked me whether my choosing to write a story about a boy who was transplanted to a small Midwest town had anything to do with my having been transplanted myself. And I was stunned, because in the entire time that I had been writing that movie, making that movie, promoting that movie, I had never made that connection, and it took this guy who had done a little bit of research about my background to draw the line to that connection. I honestly had never thought of it.

Songfacts: That's remarkable. Are there any other examples where that's happened?

Pitchford: Well, I've been writing young adult novels now. I'm just delivering my third to Putnam, and in each one of them I borrow big incidents from my childhood. The first one that I wrote was called The Big One-Oh about a 9-year-old boy turning 10, and about the disastrous events that surround his trying to throw his own birthday party. All of that was really generated by something that happened when I was a kid. My mother threw each of us one birthday party when we got to first grade, because it was the first time that we had classmates and we had friends. So as each of us turned 7, we got a birthday party, and my older brother was the first. So we were trying to figure out what to do for his birthday party.

In Honolulu, we got the tail end of any movies that came through - we didn't get first-run movies, and we didn't get the biggies. Anything that was thrown on the boat and made it across the Pacific Ocean was what we were shown as kids. We would go to the movies every Saturday, and every other weekend it was in English, and in between it was in Japanese, because of the heavy Japanese population in the islands. We went to the theatre one weekend, and we saw previews for an upcoming movie called The Giant Claw - it was about an eagle that came from outer space and was swooping down and picking up school buses filled with children and convertibles filled with teenagers and crushing them and then, finally at the ending, I think the Air Force goes out and shoots the eagle down. I think it was a Japanese movie that was dubbed into English. But anyway, my brothers and I thought it was really, really cool, so when my mom said to my brother, "What should we do with your friends when they come over?," we all went, "Oh! Oh! Let's take them to see The Giant Claw!" She said, "What's The Giant Claw?" and we said, "Oh! It's the coolest movie!" In those days you didn't have the Internet and you didn't have Cinemascore to tell you what you were getting into. So the day came and all these impressionable little kids came over, and my mom and a neighbor piled ten of them, myself and my younger brother into their station wagons and we all went off to see The Giant Claw. The girls were very squeamish about it and the boys all thought it was really cool. Then we all went back to the house and we all had our birthday cake and the parents came and took the kids home. It wasn't until the next day that parents started calling my mom and saying, "What did you take my child to see yesterday?" It turns out that one by one, these kids were waking up in the middle of the night and pointing at the ceilings of the bedrooms and screaming, "The claw! The claw!" which is what all the inhabitants of whatever town was being terrorized by the giant claw would say whenever the shadow of the eagle would pass over their city.

So my mother was very angry with us for having painted her into the corner, but my brothers and I thought it was really cool that we had thrown a birthday party that was so memorable that it was terrorizing the kids. [laughing] So I basically wrote a story about a terrible birthday party gone horribly awry, and this little boy who lives without a father and he has an older sister and a mother. He discovers that the man who lives next door who has actually been trying to romance his mom is a failed special effects creator for motion pictures, and he sort of becomes an apprentice to this man's workshop of making ghoulish special effects. So it's a kind of birthday party/horror combination, and the entire idea came out of that disastrous birthday party. It doesn't specifically quote any of the events of my older brother's birthday party, but it was certainly tucked away and came bubbling up all these years later.

Songfacts: One that is more of an overt inspiration is "Fame." You were an actor, and here you are writing lyrics to this song about becoming famous and making it as a star.

Pitchford: That was absolutely a direct line of connection. Because Fame was the first big project that I got involved in motion picture-wise as I was stopping my performing. While I was writing that, I was still making commercials, but then shortly thereafter I stopped performing entirely. But at the time it was exactly what I had been living for the last six or seven years in New York. Had I stopped that and gotten further away from it in years, perhaps it wouldn’t have been as heartfelt as it was. But both "Fame" and "The Body Electric" were both real available to me.

I got to my friend's apartment, and he opened the door and I said, "Don't talk to me! I need a piece of paper!" I went into the bathroom and I put the lid down on the toilet and I sat down on the floor, and on the toilet paper, on the toilet lid, I wrote all of what I just said to you. That came that way.

"Fame," on the other hand, was a month of writing. That was excruciating, because it was very tough to navigate. You know, the idea of fame is such a pumped up, almost self-congratulatory notion, like, I'm going to be famous. It was very tricky to navigate and write something that still had energy and gosh-golly about it, without feeling too self-satisfied.

Songfacts: Whose idea was it to trail out the "remember" in "Fame"?

Pitchford: Very clever of you. Do you know what a contractor is in a recording session?

Songfacts: No.

Pitchford: When you do a recording session, sometimes you'll get a contractor who will job out all of the musicians, or in this case you get a contractor who will do the background vocals. You find some background vocalist, and generally the person who is your background vocalist is like the team captain. He or she will come in and listen to the track and say, "I know what we have to do for this, and I know the perfect voices to pull in for this." So we hired one of the most successful background vocalists in New York at the time. He came in, listened down to the track. We got to the end of the chorus and he said, "Back it up, back it up! Check this out." And Irene Cara sang, "Baby remember my name," and he went, "Remember, remember, remember..." and we all went, "Oh! That's terrific!" And that contractor was Luther Vandross.

Songfacts: Oh, my goodness.

Pitchford: And he's the one who brought in Vivian Cherry and Vicki Sue Robinson, who was famous at the time for having had a big hit record with "Turn the Beat Around." So Vivian Cherry, Vicki Sue Robinson, and Luther Vandross are the background singers on "Fame," and Luther Vandross is the one who not only came up with "remember, remember, remember..." but he also stacked the voices on top of, "I'm going to learn how to fly high." He did that. He made a couple of other contributions around the edges, but the "remember" was the major one.

Songfacts: You were talking earlier about how the Whitman poem hit you. Have any other songs been inspired by poems or literature of some kind?

Pitchford: Well, yeah, as a matter of fact, there was a play that had been on Broadway years ago called Dylan, and it won a huge number of awards when it was on Broadway. It was about the life of the Welsh poet, Dylan Thomas. When I was in high school I competed in speech tournaments and I was a debater, but I also did dramatic interp and things like that. There was a particular long speech that Dylan Thomas gives. He's drunk and he speaks about the gift that a poet gets: he may not have a long life, but in his poems he gets to live forever. And I competed with this, I went all the way to the state finals delivering this speech. And I always loved the sentiment in poetry: if you write words, you get to live forever in your works. You know where that went.

Songfacts: Yeah. "I'm gonna live forever."

Pitchford: Yeah. And I wrote that line when Michael Gore played me the melody that he had come up with for the chorus. I listened down to it once, and I said, "Oh, you mean something like..." and he went back to the top and he was playing it down, and I sang, "Fame! I'm gonna live forever," and he stopped playing, and he went, "Oh my god! Write that down! I don't want to forget that!" And I said, "Oh, Michael, I don't think I could forget that one."

The rest of the song took forever to write. It was literally a month of six days, seven days a week, six hours a day of carving every one of those verses. But that line sprang out of my mouth.

Songfacts: You wrote "You Should Hear How She Talks About You" with Tom Snow, which I believe Charlie Dore recorded first.

Pitchford: Charlie Dore did the first cut of "You Should Hear How She Talks About You" until Melissa came along and made a hit of it.

Songfacts: How did that song come about?

Songfacts: Tell me about how you came up with the title, "Footloose."

Pitchford: Oh, that was long and involved. I had written the screenplay for the movie, and it had gone quite a long way in the development process. It was with two producers at 20th Century Fox, Dan Melnick and Craig Zadan. And the whole time I had used a working title. I just called it "Cheek to Cheek" because I knew that wouldn't be the title, but just to call it something. It was on every early draft, it said, "Cheek to Cheek," underneath parentheses, "working title." It was just instead of calling it the Untitled Dean Pitchford Screenplay. And it looked as if Dan Melnick was really going to take it all the way and get the financing going for it at Fox, which did not happen as it turns out, we left Fox and went to Paramount. But it became apparent that we'd better get serious about calling it something else.

About day 2, I wrote down "footloose and fancy free," and then I wrote down "footloose," and then separately "fancy free." When I went back over the list, I think I had four that I thought might be good ideas. But "Footloose" was by far my favorite. I typed up hypothetical title pages, and I put, "this title by Dean Pitchford," as the title of the new screenplay. Then I put the four of them in a stack, and I put "Footloose" on the bottom. I took them into a meeting with Craig and Dan, and I said, "Here are some ideas for the title." They looked at number one, they went, "Okay. All right." And they flipped it over, and number two, and they flipped it over, and number three, "Okay." And then they flipped over the last one, which was "Footloose by Dean Pitchford," and they lit up like a Christmas tree. I had deliberately done it that way, because it was my favorite and I was saving it for the end. And they felt what I felt, which was it was just such an interesting looking word and it didn't mean anything, but it did. And all those "O's" gave it a visual kind of punch. We all just went for it. It sort of sold itself. I certainly didn't have an idea for a song, because I hadn't yet gotten together with Kenny Loggins. But it's one of those interesting words that looks good on paper - you see it scrawled across a billboard, and it sells itself.

Songfacts: Tell me about writing the lyrics to that song.

Pitchford: That was interesting. I went to your website and you have half of the story on your Web site, because you talk about Kenny writing it in a hotel room. The two stories are conflated in your version, and they're actually two separate ideas. One was that he had fallen off a stage and broken a rib in Utah. He had had to cancel a number of engagements because of that, and I was supposed to be writing with him; we were supposed to have a writing date in the middle of that period when he had to come back to L.A. and recover. And after he was going to be playing Tahoe, he was going to Asia and he would not be available for three or four months.

Paramount was chomping at the bit. They wanted to know that Kenny Loggins was going to be doing the title song, and if he wasn't then we had to move on and get somebody else. So it became absolutely vital that as soon as Kenny was back on his feet, I had to go and seal the deal, and the only place that we could seal the deal, he was going to attempt to get himself back on his feet in Tahoe, play one last engagement in the States, and then go off to Asia.

Dean with Kenny Loggins

Dean with Kenny LogginsI was spraying my throat full of Chloraseptic to kill the pain and taking decongestants so it didn't sound like I had a cold or any kind of problems. I was running a fever, like 101, but I wasn't going to let on to him, because I didn't want him running out of my hotel room. I think it was two or three days we kept up this charade with him showing up on his painkillers and me on my painkillers, and us getting the gist of the song. We wrote the verses and the chorus melodies, we wrote the first verse, and we knew what we were going to do for the chorus. Then he went off and he left me with the melody for "I'm Free," which is his other contribution to the movie. While he was gone, I wrote the rest of the lyric to "Footloose," except the bridge. We finished the bridge after he came back to the States and I went over to his house, which may have been in the Valley. I was newish to L.A. so I was kind of foggy on where the neighborhoods were. But we wrote two verses and two choruses in advance, and then put the "First we got to turn you around," all that stuff was the final addition that completed the song.

Songfacts: There are a lot of words in that song, and the way Kenny sings them, you can't always understand them real clearly. How did you feel about that?

Pitchford: Well, it's funny you should say that. It was interesting, Kenny had always had a very strong idea of what he wanted the lyrics to be or what he wanted them to say. For instance, he is the one who wanted to use the name Milo: "Whoa, Milo, come on, come on, let's go." Because he liked the way the vowels sounded. Once I had cracked the back of the song with the "Oo-wee, Marie, shake it shake it for me," which was my mom's name, once we had the idea of using names throughout the chorus and calling out, "Jack, get back, come on before we crack," once that had been set up as a convention, he threw out Milo because he liked the way that the words felt in his mouth. And there may have been one or two other lines that he came up with. And he did that on several other songs that we wrote. Like, we did a song for his next album called "Let There Be Love," and he gave me a couple of not even lines, at least the ends of lines. The word that he wanted the line to end on, or the word that he wanted the high note to be on. So it was like somebody stepping up to a canvas and putting a couple of strokes of paint on and saying, "Okay, now go finish the painting," and you having to figure out how to incorporate the strokes of paint into the ultimate picture.

The way that Kenny sings, I was just so in love with the way that his voice worked around the words, I was never really aware that they were hard to understand, because I knew what the words were, and I never called him on that. But I would imagine maybe if you were listening to the song for the first time, there might be a couple of things that you go, "Come again?"

Songfacts: When I heard the Blake Shelton version, all of a sudden I was hearing it a different way. I realized that it wasn't "Sundance shoes," it was "Your Sunday shoes." That kind of thing.

Pitchford: Oh, "Kick off your Sundance shoes"?

Songfacts: Yeah. You know, you hear things differently. You write them, so you know what the words are. But people hear these in all kinds of different ways. But it sounds like you are not all that concerned about the artist having perfect diction for the words.

Pitchford: You know, this was very early on in my career, and I became much more of a lyric policeman as my career went on. To give you an example from the early part of the career and later, when I did "Fame," it never occurred to me that anybody would mishear Irene Cara sing, "People will see me and cry, Fame!", but people have misheard that as "die." And I was horrified to find that lyric sites would write out the lyric to "Fame" and state as if it were fact that I had written "people will see me and die." No. I had written "people will see me and cry, Fame!" That would be their cry.

On the other hand, Tom Snow and I wrote a song called "If I Never Met You," which Barbra Streisand recorded on her A Love Like Ours album - that was all the love songs when she got married to James Brolin. She was in the studio working with our friend Jay Landers, and they called Tom and me late one night, and they played us the track as she had recorded it. When they played it for me, there was one lyric I wasn't understanding correctly, and she had also mis-sung a note, and I pointed them out. She was very grateful, and she went back and she corrected both of them. After I got off the phone with her, the phone rang and it was Tom. He said, "So did you hear it? What did you think?" and I said, "Well, I was very happy except for this and this." And he said, "You didn't say anything, did you?" I said, "Absolutely, I said something." He said, "You gave notes to Barbra Streisand?!?" I said, "Yes. She called asking for notes, so I gave her notes. We're all collaborators in this. This is going to be the definitive version of the song, and I want it to go out there correctly sung." And he said, "I was just so wowed by the vocal that I didn't have anything to say." I said, Well, that's the difference. I was wowed, but at the same time, I had learned from sorry experience that rather than going, "Oh, wow, somebody's recording our song," that there comes a moment where you have to get really clear eared - not clear eyed, but clear eared - and listen to it with a real critical faculty and say, "Great! Everything is terrific except this and this." And let's go forward with the most accurate version of the song we possibly can. So whereas I let Irene Cara slide all those years before, I jumped on Barbra Streisand when she offered me the chance. And she was gracious about it. She was just so lovely about it. The thing I've discovered over the years of working with Barbra is that she really wants to be involved in a creative give-and-take. She likes when she's got conversation started.

Songfacts: "If I Never Met You" was a very personal song for you, wasn't it?

Pitchford: It was, actually. When I met my husband of 21 years now, about 6 or 8 months after we met, Michael Gore and I had an international hit with Whitney Houston with "All The Man That I Need." Michael (Dean's husband) was on a swim team at the time, and a lot of his teammates, knowing that he had just met me, joked, "Oh, you've only known Dean a short time and already he's written a song about you," because it was all over the radio for months and months. And that wasn't the case. I had written that song with Michael Gore years before starting for an artist named Linda Clifford, who recorded it - Linda Clifford whom we had worked on "Red Light" in Fame. We then wrote an album of material and Michael produced an album of material on her, and we wrote "All The Man That I Need" for that album, and then it was subsequently recorded by Sister Sledge as a duet, and then it was recorded by Whitney Houston and then it was recorded by Luther Vandross.

It was such a good experience working with Barbra that when she next did a Christmas album, she asked us to write a song for it. So the album A Christmas Memory has a song that we wrote called "Closer."

Songfacts: "All The Man That I Need," was that a personal song, or was that one where you got yourself into character?

Pitchford: Michael Gore and I knew we were writing for Linda Clifford, and we wrote the album in the way that you would write any kind of an album, where we had our up-tempos and we had our ballads, and we needed a ballad to balance everything out. So that definitely fulfilled that particular need. It was a luxury to be able to write an array of songs and try to cover all the bases. You didn't want to write an album's worth of ballads or an album's worth of up-tempo. Linda Clifford had been known as a disco diva - she had a big hit with a disco version of "If They Could See Me Now," and then she had a hit with our song, "Red Light," and then even off of that album that Michael and I worked on with her, she had a hit called "Don't Come Crying to Me." Her biggest fan base was the dance clubs. But we knew we needed a ballad for her, so "All The Man That I Need" specifically addressed that need.

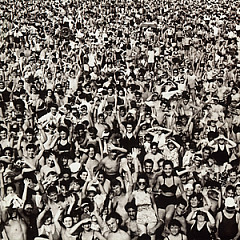

"Footloose" Feb. 11, #1

"Holding Out for a Hero" Apr. 7, #34

"Let's Hear it for the Boy" Apr. 14, #1

"Dancing in the Sheets" Apr. 14, #17

"Almost Paradise" May 19, #7

"I'm Free (Heaven Helps the Man)" June 23, #22

"Almost Paradise" was a #1 Adult Contemporary hit. "Let's Hear It For The Boy" was a #1 R&B hit. The soundtrack album unseated Thriller at #1 and stayed there for ten weeks.

Pitchford: Well, I was in the unique position of having written the motion picture, the screenplay. I had also in my head mapped out every place that there was going to be a song in the motion picture. I had not written the songs, but I had models for each place where there was going to be a song. So I knew where there was going to be a dance number, I knew where there was going to be a pop number or rock and roll number or ballad. I was working with a wonderful musical supervisor, Becky Shargo, who is now Becky Mancuso. It was not a case of trying to hit as broad of a target as possible, but it was a case of trying to avoid repeating ourselves. And in doing so, I wrote the R&B song, which was "Dancin' In The Sheets," which we ended up getting Shalamar to record. And then there was a rock & roll song, which was Sammy Hagar - he and I wrote "The Girl Gets Around." It wasn't specifically an attempt to cover all these bases, but it was an attempt not to repeat ourselves.

When we finally went down the list and ticked off, I got a pop tune here, I got an R&B song there, I've got a soulful ballad here, I've got a duet ballad with "Almost Paradise." We ended up having an album that cut across all these genres - we had songs on the adult contemporary charts, the Billboard Hot 100, on the dance charts, on the rock & roll charts with Sammy Hagar. It ended up becoming a bonanza for Columbia Records at the time.

In that case I was very hands-on because I wrote the movie, and I wrote all the lyrics to all the songs. So I had a big say in all of that. I think a lot of album soundtracks these days are put together by music supervisors, and I don't know that they think that way. I know that there's a big emphasis on getting the biggest acts and the biggest radio potential on those soundtracks.

Songfacts: It's interesting that you talked about getting a different sound for all these different places in the movie. It meant you had to work with a lot of different writers and artists. When you were working with these different collaborators, did they have to adapt to you or did you adapt to them?

Pitchford: I didn't want them to adapt to me. I wanted to adapt to them because I was coming to them for their sound. So in every case where we had decided on an artist that we were going to approach, I went to school on the style of the writer that I was going to be working with. In the case of Sammy Hagar, I went back and I listened to Van Halen stuff over and over and over again, and then a lot of his stuff.

Songfacts: "Almost Paradise," Eric Carmen was the artist and the writer. How was it working with him?

Pitchford: Well, he wasn't the artist on it.

Songfacts: Oh, that's right. I was thinking, because you did the song later, "Make Me Lose Control" with him.

Pitchford: Right, exactly. But at the time I don't think Eric was on a label. I think Eric was in a kind of a cooling off period in his career and had left his label. He really came roaring back when "Hungry Eyes" went on to the Dirty Dancing soundtrack, and then Arista signed him up again. He wasn't viable as an artist, but he was one of my favorite, favorite songwriters. I always thought that Eric Carmen was a beautiful melodist. Look at "Boats Against the Current," look at "All By Myself." Gorgeous, gorgeous stuff. And so he flew in from Ohio and agreed to write with me, but we had no idea who the artist was going to be. But we turned out a song that a lot of people wanted to record, and we were able to get Ann Wilson of Heart and Mike Reno of Loverboy. Being able to snag two of the monster voices in '80s pop music was a real feather in our cap. But again, that was simply a case of I knew we needed a ballad, I knew we needed a duet, and I knew that Eric Carmen was the guy to deliver the high emotion of that. And then after that it was just a case of shopping it and we got answers right away, emphatically, from those two.

Songfacts: Was he the guy who called you to work on "Make Me Lose Control"?

Pitchford: Oh, yeah. Eric and I are still friends to this day. I still remember the moment: I had a one bedroom bungalow in West Hollywood, and we were seated in the living room, and we were tossing out ideas. I had come in with the title "Almost Paradise," because I had been riffing on a lot of titles that had to do with religion and salvation, very much in keeping with the tone of the minister and the preacher and the church background of the motion picture. So "Almost Paradise" was the given. But I remember sitting there and tossing out lines and coming up with, "I thought that dreams belonged to other men, because each time I get close they'd fall apart again." And he liked that very, very much. I was sitting there and I said, "Oh, how about this, 'I feared my heart would beat in secrecy'?" And he jumped up from the keyboard and he ran over and he hugged me, and he said, "That's fucking GREAT! That's one of the most brilliant lines I've heard!" And he said, "We've got to do a lot more of this writing." And it was that line, "I feared my heart would beat in secrecy" that sort of joined us at the hip. From that point on, we wrote all day.

That song was written in a day, but in an 11-hour, 12-hour day. The next morning we went into the studio and into the office of our director, who had an upright piano installed in his office specifically to hear all the songs as I created them, with my various collaborators. Eric and I went in and we sang - I brought a girlfriend of mine in to sing the female part, and Eric sang the male part, and that sold that song. I remember bringing in a girl to sing "Holding Out For A Hero" with Jim Steinman pounding the crap out of the keyboard. When we were done, I looked over and there was blood on the keys. That's the kind of "DUN DUN DUN DUN DUN da DON DON DON da DA DUN." He was just pounding the shit out of the keyboard. Everybody was just grooving along as he's pounding and this girl's singing, singing, singing. And at the end of the whole thing I looked over and there was blood up and down the keyboard. It cut his fingers.

Songfacts: You were talking about the church theme and making these songs fit with the movie. "Dancing In The Sheets" makes me think of a very clever play on "Dancing In The Street." Was that your concept?

Pitchford: Oh, yeah. Absolutely. Well, the thing is, if you remember in the movie, it was the song that was playing at the drive-in that the minister's daughter had smuggled the tape in. So I knew it needed to be naughty enough that her father might have an objection to it. But I also had long wanted to do a play on "Dancing in the Streets," and I thought that there was something kind of wink-wink naughty about that. And it needed to be suggestive enough that it would provoke her father's ire, but not vulgar in an over-the-top kind of way.

Pitchford: Right. And they didn't want to use the Johnny Mathis song. And so you're right, we had to write around that.

Songfacts: So how did you go about doing that and coming up with that song?

Pitchford: That was really a case of my taking a lyric to Tom. The theme of the movie, if you know the movie, it was about a woman who falls in love with a man only to lose him. He gets killed, and then his soul migrates into another body and comes back in a younger man. And that soul is trying to reunite with her, but inevitably she ends up with a man who has been staying by her side all her life, and has been there for her. And that's the soul match that was to have been made. So when she walks down the aisle at the end of the movie with Ryan O'Neal, it's the end of a long journey. So I wrote "After all the stops and starts, we keep coming back to these two hearts. Two angels who've been rescued from the fall." I thought that that was really the summation of the movie, because you get some scenes in Heaven, where the soul gets misassigned. And I always liked the idea of angels being rescued from the fall, and I also liked that "fall" rhymed with "all." So I brought Tom the "After All" concept of "we keep coming back to these two hearts," and that was the taking off point.

Songfacts: The last thing I have for you, Dean. A lot of your collaborators have talked about how this comes easy for you. Does it?

Pitchford: Oh, no. No, it doesn't come easy. Sometimes when I walk into a room and we write - like Eric and I did "Almost Paradise" in 11 hours - that's the result of weeks of preparation. I don't come up with a title, "Almost Paradise," easily. Sometimes something will pop into my head, but most often, if I can title a song, I can write it. But it can take me days and days and sometimes weeks to title a song. If I can title it and I can tell you the story of it, then I can write it. But titling a song was very, very hard for me. That's why I would keep books filled with title ideas. I would write stuff down in the middle of the night and I would transfer it to the books and I would carry these things around with me and I would add to them on airplanes. And when I was a signed writer to Warner Brothers, they would fly me to Nashville to write with their other signed writers - maybe twice a year I'd go in and have a week where one day I would work with this guy and one day I would with the next guy. Every day I was moving to another office and working with another writer, and I had to have all of my stories with me. Sometimes another idea would come out of it, but it would definitely have been spurred by all the groundwork that I had laid.

So no, it might come together quickly, but the coming together is only the result of a lot of spade work.

Pitchford: I don't know what you mean. You mean a melody?

Songfacts: You talked about how you have to have a title to do a song. I was wondering if you ever came up with a story and you had a song there, but you couldn't come up with a title.

Pitchford: No. Because everything in a pop song, everything, all the roads point to the title. Everything leads to the title. And if I can build that title, then everything can build out from that. What I would have problems with is when Tom Snow or Michael Gore or sometimes Peter Allen would give me a melody. Sometimes my collaborators would just give me cassettes with a melody with them going, "la la la," and I would listen to it over and over and over and over and over again trying to find the best possible title. I was always sort of known for having interesting titles, like "Almost Paradise," like "You Should Hear How She Talks About You." And if I could title the song, I could write it, but it would sometimes take me forever.

I used to have a technique where I would put the song into a cassette and I would put it on a loop. I would reproduce it several times so it would play maybe five times on the cassette. Then I would put it on a cassette player outside the shower and I'd go into the shower. I would hit Play and I would listen to it through the shower. It was like you're trying to look at an object and trying to discern the object, and you cross your eyes, and you try to see it. This was my way of smudging it: what am I hearing here? I'm not hearing it exactly, but I'm hearing kind of a version of the melody, a version of the title line. Then I'd get out of the shower and I'd write down all these title ideas that I'd had while I was listening, like I was crossing my ears.

Songfacts: Is there a specific song you can remember doing that to?

Pitchford: I think it was "Don't Call It Love." A song I wrote with Tom Snow that was first recorded by Kim Carnes and then became a hit for Dolly Parton. And we eventually won the BMI award for the most-played country song of the year in 1986 for "Don't Call It Love." But that was very early in our collaboration. He'd given me this really cool track, and I was having a dickens of a time trying to title it. I did everything. I played it before I went to sleep, I played it when I got up in the morning, I played it outside the shower stall, I played it in my car. And the eventually I came up with the title. But I use that technique a lot.

March 13, 2012

Dean has a great website at deanpitchford.com. Photos courtesy of Dean Pitchford.

More Songwriter Interviews