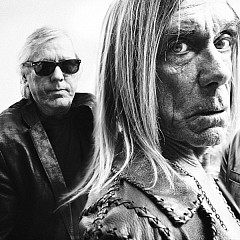

Through his archive of interviews with songwriting legends, renowned music journalist Bruce Pollock tells their stories in their own words. This is taken from his 1989 interview with Graham Nash.

Before the pandemic, I looked over Graham Nash's touring itinerary and identified a few dates where he could conceivably cross paths with the band he co-founded, The Hollies. But it's more than distance - and a second huge career with Crosby, Stills and sometimes Young - that separates Graham Nash from his Manchester pals. "During my time with The Hollies I began to feel I was doing a kind of disservice to music," he relates in this 1989 interview, "in that these songs weren't telling people how to deal with life out there. They weren't letting people know about how another individual felt about falling on his face, falling in and out of love, being outraged about what was happening to us from the government or from this side or that side. But I feel I've kept very true to my own particular feelings ever since."

Before the pandemic, I looked over Graham Nash's touring itinerary and identified a few dates where he could conceivably cross paths with the band he co-founded, The Hollies. But it's more than distance - and a second huge career with Crosby, Stills and sometimes Young - that separates Graham Nash from his Manchester pals. "During my time with The Hollies I began to feel I was doing a kind of disservice to music," he relates in this 1989 interview, "in that these songs weren't telling people how to deal with life out there. They weren't letting people know about how another individual felt about falling on his face, falling in and out of love, being outraged about what was happening to us from the government or from this side or that side. But I feel I've kept very true to my own particular feelings ever since."When he started, it was certainly a different time in the pop culture scheme of things, with The Beatles reinventing the Top 40 single. "The bulk of the songs were either written by me or by Allan Clarke, with little additions by Tony Hicks. I remember doing 'On A Carousel' in a bar room in Margate, this seaside town in England. Somebody would say, 'hey, carousel,' then it would go round and round and we'd end up with a song. Everything was pretty light, lyrically shallow. So, you would be able to think of something and write a pop song to it. You could really manufacture songs about anything. You develop a vocabulary of hooks and you swing two hooks together. It's a technique that can be learned. I don't think anybody just naturally writes that kind of song."

A pivotal song for Nash back then was "King Midas In Reverse," after which the Top 40 experience began to seem hollow. "I started to change radically," he says. "I began to get more private in my thoughts. I began to dig deeper. I began to realize that songs could become interesting ways of letting your feelings be known. At that point I wrote songs like 'Marrakesh Express,' 'Lady Of The Island,' and 'Right Between The Eyes.' The Hollies wanted to continue with the formula they'd successfully established over the years. But I think they could sense I was unhappy."

The Hollies ultimately rejected "Marrakesh Express," which wound up on the first CSN album and hit the Top 30 as a single. The Hollies version of the song was never finished. "I haven't heard the tape for years, so I'm not quite sure how it turned out," Nash says.

Whereas the Hollies released five albums between 1967 and 1968, Nash's next venture, with David Crosby, Stephen Stills (and the occasional Neil Young) had a much slower creative pace. After putting out three #1 albums in a row as CSNY between 1970 and 1974, the guys waited three more years to release another album, dropping Y in the process. Resting on their laurels and their royalties (and their separate yachts) they waited another four years before their label issued Replay, a greatest hits album that went nowhere in 1981. Scared nearly straight by this turn of events, the three remaining gentlemen knuckled down to produce Daylight Again a year later, which brought them back to the Top 10 for the first time in five years. It would be their last visit to the upper reaches of the albums chart, though CSN would unite again with Y for American Dream in '88 and Looking Forward in '99. Graham Nash, for one, as far back as '82 understood that the ultimate super group had squandered much of their goodwill.

"With 'Wasted On The Way' I realized how much time CSN had wasted," he says. "You must understand that CSN had only put out four albums in 14 years. That's a tremendous popularity to be bestowed on anyone with so little credit. We'd wasted a lot of time and done a lot of fighting, a lot of staying away from each other deliberately. With songs like 'Darkness' and 'Wasted On The Way,' I anticipated what would happen to us if things continued going the way they were going."

"With 'Wasted On The Way' I realized how much time CSN had wasted," he says. "You must understand that CSN had only put out four albums in 14 years. That's a tremendous popularity to be bestowed on anyone with so little credit. We'd wasted a lot of time and done a lot of fighting, a lot of staying away from each other deliberately. With songs like 'Darkness' and 'Wasted On The Way,' I anticipated what would happen to us if things continued going the way they were going."The laurels they rested on, however, were some of the finest laurels in pop history. Nash was able to tap his inner Donovan to pen immortal singles like "Teach Your Children," "Chicago," "Just A Song Before I Go," "Our House," "Cathedral," as well as "Wasted On The Way."

"I never did get out of the habit of writing short songs," he says. "I was trained by Tin Pan Alley and by radio and by attention span and by how much a particular DJ would play of a particular song, to write two- to three-minute songs. Whether that's the unknown attention span of most listeners I couldn't say, but it seems to be a magic number. I'm sure if you look back at all the Beatles songs you'll see most of them are two or two-and-a-half minutes."

He was also afforded the luxury of incorporating the Phil Ochsian side of his personality into his songwriting, with what he called "songs as news."

"That's a great term, 'songs as news.' Because, with songs like 'Chicago' and 'Ohio' CSN began to reflect the environment in which we were totally immersed at that point. During the mid-to-late '60s it was crazy in America. Society was stretching out. It was having birth pains. People were beginning to realize that they were trod upon in many ways. And, for instance, in 'Chicago,' when I saw them bind and chain Bobby Seale to a chair and put a gag in his mouth and put him in the witness box and try to call that a fair trial, every fiber of my Englishness said, 'Wait a second, that's just not fair.' So, songs as news, and the news is that people have individual feelings. They want to hear songs that mean more to them than 'Hey Carrie Ann, what's your game.'"

Rarely do songs come into Nash's mind fully formed. "I've written songs and made records from every angle I can think of. I've done instant songs, right on tape, building the track up from a kick drum. And I've done songs with orchestras. I've had the end of the song first and filled in the front and the middle. Songs like 'Teach Your Children' and 'Wasted On The Way' came out just as they are. 'Wind On The Water' and 'Cathedral' took me three or four years to write. Obviously, I wasn't constantly working on those songs for four years, but I was waiting for the thoughts to come flying through.

"I can't just sit down and say, 'OK, now I've got this one verse and chorus to go on 'Wind On The Water' and I'll be finished.' I've got to wait for it to come. To me, the songwriting process is one of almost a conveyer belt system. I have maybe a dozen pieces of music all waiting for a verse or a chorus and they come off the conveyer belt at their own rate. I might have a verse or a chorus of a particular song, but I'm waiting for something to happen to me, so I can go, 'Wow. I can use that right now.' Then I get a pen and write it down."

Adding to his Rock and Roll Hall of Fame work with the Hollies and CSN&Y, Nash has written a memoir, Wild Tales: A Rock & Roll Life, which was published in 2013. This Path Tonight, released in 2016, is the most recent of his solo albums. He refers to it as his "divorce album," in which he confronts his personal split with his wife and his final business split with the erratic Crosby.

But his relationship to the songwriting muse is ongoing. "In most cases it's a thought process that's lyrically inclined," he reveals. "Then the music comes later. I have very rarely written a song without words and then put the lyrics to it later. Most of it has been something I had to say and then I found a way musically to say it. I write for myself. I'm a very selfish songwriter. I write to exorcise my own devils, to provide myself with the services of a self-contained psychiatrist. I've saved a lot of money by being able to write songs, because I talk to myself in my songs. I don't like to collaborate, because to collaborate you have to let somebody else into your mind and I'm not sure I want to do that. I have certain things, for instance, certain choruses that I know are really great. When they finally get sculpted into a final piece, they'll be fine, fine pieces of music. I'm very loathe to say to someone, 'I've got this thing, what do you think?' I'm selfish like that."

October 23, 2020

Further reading:

Bill Withers

Dave Mason

Laura Nyro

photos: Amy Grantham

More Songwriting Legends